Artificial, yes. But, Intelligence?

Co-authored by Lex Gorecki

Recently, The Wall Street Journal (WSJ) expressed concerns about Chinese military advances in the field of Artificial Intelligence (AI), mentioning a system that can scan video captured by drones and find details a human analyst would miss. Such systems could, for instance, identify a particular individual moving between previously undetected terrorist safe houses.

The WSJ concluded that the U.S. now finds itself in an escalating AI arms race: “Over the past two years, China has announced AI achievements that some U.S. officials fear could eclipse their own progress.” In other words, the media tell us that the time has come to be concerned – and not just in the military sphere, as the impact of AI on business, including retail, will also accelerate.

Having attended a number of retail conferences in recent months, we have observed growing chatter about AI, with some vendors and consultants claiming that it will completely transform the industry. The media has jumped on the bandwagon and fuels this narrative, oscillating daily between painting AI as ‘creating the future’ and ‘collapsing the market’.

In this case, the media can be forgiven for its Jekyll and Hyde headlines, due to the staggering amount of misinformation surrounding AI. In particular, the preoccupation with the progression toward anthropomorphising AI routinely confounds even the brightest minds.

In the past, we have rarely mentioned AI in relation to retail, as it had little relevance to the industry. However, given all of the AI rhetoric in the field today, the time has come to examine the matter.

Let’s start by exploring what the term AI actually means.

The true meaning of AI

The first intriguing take on AI can be traced back to the early 1960s, when Stanislaw Lem examined the concept in his book titled Summa Technologiae. Lem made an important distinction, postulating that we ought to pursue Artificial Instinct rather than Artificial Intelligence.

Distinct from Artificial Intelligence, Artificial Instinct can be understood and built using today’s science and technology, while still promising incredibly smart machines. On the instinctual level, even simple animals display exceptional abilities. After all, they operate in the real world on their own, proving that a living being doesn’t need human-level intelligence to survive.

Lem did not suggest Artificial Instinct as simply an attainable alternative to Intelligence. In fact, at no point did he declare humanity incapable of creating Intelligence. He just saw no need for Intelligence, when in his view Instinct would suffice. He also expressed serious concerns about the dangers of Artificial Intelligence.

Let’s consider the core differences between Artificial Instinct and Artificial Intelligence.

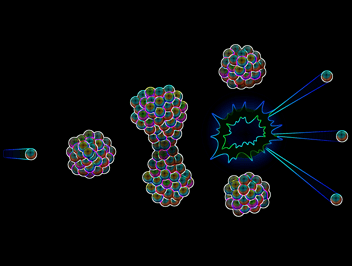

Artificial Instinct can be blue-printed as algorithmic behaviour, stemming from the structure of the nervous system and the physical design of the specific animal. Albeit still quite complex, such natural design patterns can be reproduced using man-made computers and machines. The example of the nematode worm C. elegans illustrates this well – an organism that has been transplanted wholesale into software, yet retains its real-life behaviour driven by nothing but its wiring.

However, on its own, this will not deliver Artificial Intelligence. For a machine to qualify as truly intelligent, it would need to have the ability to think and behave irrationally. Such behaviour stems from human emotions and the ability to think in abstract terms.

Arguably, this cannot be recreated in machines – and even if it could be, why would anyone want to build an artificial being that could act in an unpredictable and possibly dangerous way? Who needs neurotic or psychotic machines?

AI in daily life

Artificial Instinct, with its algorithm-driven behaviours, has become commonplace today. From GPS route optimisation to house-wide climate control, little software ‘critters’ change their behaviour according to varied inputs (traffic jams, temperature sensor reads) and a simple set of rules. The ones that learn how to make their own sets of rules, therefore working better over time, have been cited as examples of ‘AI’ in action.

The present and near-future trend that has people so focused on AI stems mainly from the morphing of software and immobile-hardware applications into mobile hardware – with driverless cars on one end of the spectrum, and quadrupedal robots opening doors (oddly reminiscent of the Velociraptor scene from Jurassic Park) on the other. Suddenly, ‘AI’ can move under its own power, and make instinctive decisions, in places where bystanders could get hurt. Just a few days ago, on the 20th of March, news.com.au reported that a self-driving Uber car killed a pedestrian. No wonder AI sensationalism continues to rise.

However, in the software space, very little has changed. AI hasn’t suddenly grown morals, or a limbic system, or really changed in any qualitative sense. It won’t produce artists or philosophers any time soon.

Exit AI, Enter ASM

The above leads us to the conclusion that the IT industry, scientists and academics claiming to be developing AI have, in reality, been focused on something else over the past few decades. What they actually pursue can be best described as ASM – Animated Smart Matter. Smart machines functioning in the real world, which create illusions of intelligence.

Examples of ASM can be found everywhere, in varying degrees of complexity. For example, a bridge span bends in order to handle a load, and then flexes back to its original shape once the load has been removed. Such a simple machine adds a lot of value and remains benign. However, a more advanced ASM machine – running on a more complex set of Instincts – could become much more capable, and potentially sinister.

At its core, ASM redefines ‘AI’, stripping it of (unnecessary) emotions, an ego, a conscience, or any of the related ethical and moral dilemmas. The quest for AI aims at increasing the capability of the Instincts running the show, making them finer and more specialised and – in the process – more inscrutable.

Machines with such mindless ‘smarts’, especially when scaled up and mobile, will be capable of anything – good or bad. And, with the number of ‘black boxes’ already out there, proving that any given ASM machine can be classified as ‘safe’ will be a tall order. This needs to be addressed, and control mechanisms must be put in place to make ASM advancement less threatening. Media, industry leaders and politicians frequently highlight the potential dangers.

In our assessment, governments and regulators should stop debating what limits to impose on AI research and instead figure out how to link infractions committed by machines to the humans behind them. AI technologists need to be held responsible for the damage caused by the tools they create and use, no matter how smart. Claims that a machine independently malfunctioned must be rejected by the courts of law – the blame must rest squarely on the manufacturer.

A simple rule needs to be adopted: if you cannot predict the machine’s behaviour (or define its constraints), don’t build it. We have little doubt that ASM will evolve exponentially over the coming decades. Let’s hope that the legislators will stay ahead of this critical technological growth curve.

What does this mean for retailers?

ASM will continue to progress, but don’t let the media frenzy convince you that Artificial Intelligence has arrived and that your retail operations will be doomed without it.

Don’t expect a machine to out-think you or steal your job any time soon. Mobile machines can be useful in warehouses, but we won’t see them working the shop floor for at least another ten years. However, the non-animated automation of repetitive tasks, predictive logic and smart systems in general can materially bolster many areas of your business.

Start thinking in terms of Smart Matter and Smart Machines rather than the buzzword-prone AI. Focus on implementing systems to handle laborious and computational tasks, such as the assessment of stock on hand versus model stock, to determine store replenishment (e.g. with 100,000 SKUs and 1,000 stores you would need to make about 100 million decisions. This can then drive smart machines to locate and pick the required stock in the warehouse.

Once you automate such tasks, you can augment your systems with smart algorithms – but keep them under human jurisdiction. For example, you can implement a system that predicts likely sales and then recommends stock movements between stores, to increase the overall probability of selling the stock at full price. However, such recommendations must be reviewed by a merchant before they can be sent to the stores for action.

These two approaches combined (automation + computer-supported decision making) will give you more retail power.

Beware of the proverbial greener grass

Note that none of the above qualifies as something new. These concepts have been around for decades, but retailers often religiously pursue various ‘Holy Grails’ instead of taking advantage of what they already know.

In our experience, the promise of a sleek technological cure for all operational and trading woes often wins favour with retailers over the organisational discipline and hard work needed to improve the base of their business. Yet, most such ‘cures’ leave retailers with a bitter aftertaste.

Let us repeat our earlier warning: don’t succumb to the fear of missing out. Yes, Information Technology looks increasingly overwhelming, but only because computers continue to get faster, cheaper and smaller – proliferating throughout ever more aspects of our surroundings.

Yet the core elements of IT have not changed. We just hear more noise about technology due to the relentless diffusion of IT throughout our world, and through the proliferation of the ‘intelligence illusion’. The latter stems from advances in voice recognition and voice synthesis systems. Arguably, navigation, game-playing and climate-control systems would be much better at what they do if their programmers didn’t insist on trying to shoehorn in the ability to hold a conversation with their owner.

Human-level General AI or passing the Turing Test have little relevance anymore. Instead, shift your focus to the thousands and millions of little subroutines – each of which can do its specific job better than a human ever could – and benefit your business. And realise: all these subroutines rely on the same core concept that enabled the AI boom in the 1980s and has been around since 1943.

Make sure that you regard IT as a tool to be used in your business, not the other way around. Don’t let the tail wag the dog.

————————————

Co-author

Lex Gorecki joined Retail Directions in 2014 as a Software Engineer, working in the areas of retail, price management, and eCommerce Content Management. He has a Bachelor of Science degree in Quantum Physics and Applied Mathematics from Monash University. His interests include neurosciences and AI.